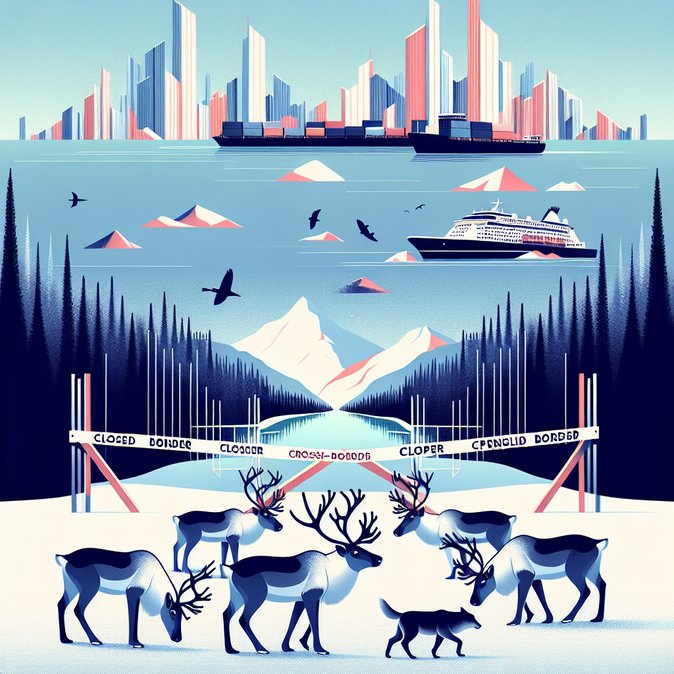

Record reindeer losses in Finland’s eastern provinces have thrust the long-closed Finnish-Russian land border back into the national spotlight—this time not over asylum-seekers but migrating wolves. A Guardian report published on 24 January revealed that predators killed more than 2,100 semi-domesticated reindeer in 2025, the highest toll ever recorded. Herders blame an influx of Russian wolves, whose numbers have reportedly rebounded as hunters were redeployed to the Ukraine front.

Although the casualties concern livestock rather than people, the episode illustrates how prolonged border closures can have unintended consequences for mobility and security. Since Finland sealed all road crossings in December 2023 to stop what it called “instrumentalised migration,” cross-border cooperation on wildlife management has collapsed. Researchers say the lack of joint monitoring allows packs to roam undetected until they strike herds deep inside Finnish territory.

For individuals who do have legitimate reasons to cross into or out of Finland—scientists monitoring wildlife populations, seasonal tourism staff, or business stakeholders—VisaHQ offers a fast, reliable way to navigate the evolving visa requirements. Its online platform (https://www.visahq.com/finland/) aggregates the latest entry rules, documents and fees, helping applicants submit error-free requests and stay compliant with Finnish regulations.

![Borderland Wildlife Crisis Spurs Debate on Finland–Russia Frontier Controls]()

For the indigenous Sámi community and Lapland’s winter-tourism operators, the economic stakes are high. Reindeer husbandry underpins local livelihoods and provides the seasonal labour that keeps hotels, guide companies and airports functioning. Heavy predation could drive herders to abandon traditional grazing areas, altering workforce availability and jeopardising visitor experiences that depend on reindeer-based culture.

Policy makers in Helsinki now face pressure to balance border security with cross-border environmental data-sharing. One proposal floated by the Natural Resources Institute is a limited-scope frontier corridor that would allow biologists—but not regular travellers—to tag and track wolves on both sides. Interior-ministry officials acknowledge the idea but insist that any movement across the border must respect the current closure decree.

The incident is a reminder that mobility management is not only about visas and airplanes; disrupted ecosystems can cascade into labour shortages and supply-chain gaps. As Finland finalises its 200-km border-fence project, experts urge a parallel investment in transboundary wildlife governance to prevent environmental issues from morphing into economic ones.

Although the casualties concern livestock rather than people, the episode illustrates how prolonged border closures can have unintended consequences for mobility and security. Since Finland sealed all road crossings in December 2023 to stop what it called “instrumentalised migration,” cross-border cooperation on wildlife management has collapsed. Researchers say the lack of joint monitoring allows packs to roam undetected until they strike herds deep inside Finnish territory.

For individuals who do have legitimate reasons to cross into or out of Finland—scientists monitoring wildlife populations, seasonal tourism staff, or business stakeholders—VisaHQ offers a fast, reliable way to navigate the evolving visa requirements. Its online platform (https://www.visahq.com/finland/) aggregates the latest entry rules, documents and fees, helping applicants submit error-free requests and stay compliant with Finnish regulations.

For the indigenous Sámi community and Lapland’s winter-tourism operators, the economic stakes are high. Reindeer husbandry underpins local livelihoods and provides the seasonal labour that keeps hotels, guide companies and airports functioning. Heavy predation could drive herders to abandon traditional grazing areas, altering workforce availability and jeopardising visitor experiences that depend on reindeer-based culture.

Policy makers in Helsinki now face pressure to balance border security with cross-border environmental data-sharing. One proposal floated by the Natural Resources Institute is a limited-scope frontier corridor that would allow biologists—but not regular travellers—to tag and track wolves on both sides. Interior-ministry officials acknowledge the idea but insist that any movement across the border must respect the current closure decree.

The incident is a reminder that mobility management is not only about visas and airplanes; disrupted ecosystems can cascade into labour shortages and supply-chain gaps. As Finland finalises its 200-km border-fence project, experts urge a parallel investment in transboundary wildlife governance to prevent environmental issues from morphing into economic ones.