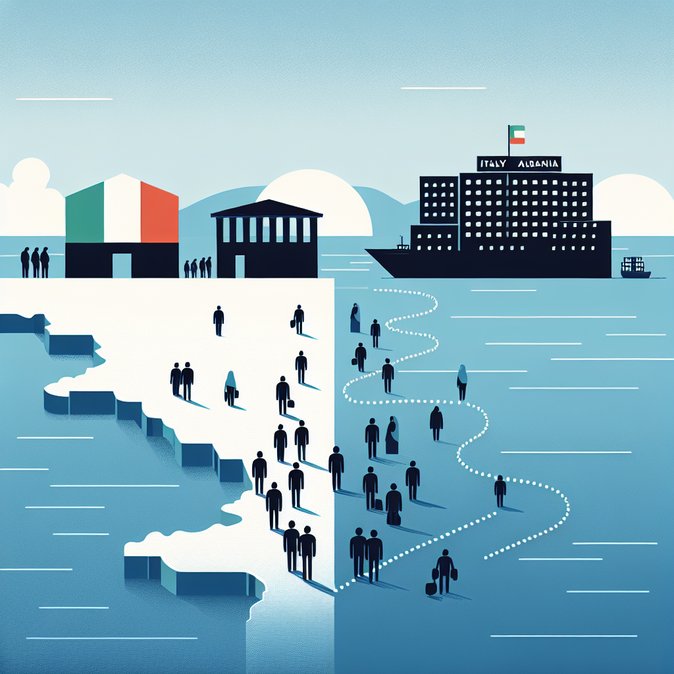

Italian prime minister Giorgia Meloni used the first Italy-Albania inter-governmental summit in Rome on 13 November to announce that her government will “re-launch” the controversial plan to process up to 36,000 asylum seekers a year in two Italian-run detention centres on Albanian soil. The scheme—signed as a bilateral protocol in 2023 and conceived as a way to deter irregular Mediterranean crossings—was derailed when Italian courts ordered the immediate return of the first 16 migrants transferred to Albania in October 2024 and when the EU Court of Justice ruled in August that fast-track offshore screening was incompatible with current EU asylum law.

Meloni told reporters that the centres “will operate exactly as they should” once the EU Pact on Migration and Asylum enters into force in mid-2026, suggesting that the forthcoming EU rules on border procedures will give Rome fresh legal cover. Her Albanian counterpart Edi Rama confirmed that Tirana remains committed to hosting the facilities, which would be staffed and policed by Italy under Italian jurisdiction.

![Meloni Defies Courts, Vows to Revive Italy-Albania Offshore Asylum Processing Scheme]()

Human-rights groups, including Amnesty International and the International Rescue Committee, have condemned the plan as a harmful offshoring model that denies asylum seekers full access to EU legal protections. Legal scholars warn that even after the new EU pact takes effect, any renewed transfers could face immediate injunctions if individual safeguards are not demonstrably upheld.

For corporate mobility managers the announcement is a signal that Italy intends to keep migration control at the top of its political agenda in the run-up to the 2026 EU rules. Companies relocating talent to Italy should expect heightened political debate and possible procedural changes at Italian ports of entry as authorities test new workflows. Organisations running CSR or pro-bono initiatives that work with refugees in Italy may need to review advocacy strategies and budget for potential legal aid.

Practically, the continued uncertainty means that volumes at mainland reception centres are unlikely to fall in the short term, so appointment backlogs at immigration offices (Questure) may persist through 2025-26. Employers should plan for longer lead-times on permit renewals and factor possible media scrutiny of asylum issues into expatriate-risk briefings.

Meloni told reporters that the centres “will operate exactly as they should” once the EU Pact on Migration and Asylum enters into force in mid-2026, suggesting that the forthcoming EU rules on border procedures will give Rome fresh legal cover. Her Albanian counterpart Edi Rama confirmed that Tirana remains committed to hosting the facilities, which would be staffed and policed by Italy under Italian jurisdiction.

Human-rights groups, including Amnesty International and the International Rescue Committee, have condemned the plan as a harmful offshoring model that denies asylum seekers full access to EU legal protections. Legal scholars warn that even after the new EU pact takes effect, any renewed transfers could face immediate injunctions if individual safeguards are not demonstrably upheld.

For corporate mobility managers the announcement is a signal that Italy intends to keep migration control at the top of its political agenda in the run-up to the 2026 EU rules. Companies relocating talent to Italy should expect heightened political debate and possible procedural changes at Italian ports of entry as authorities test new workflows. Organisations running CSR or pro-bono initiatives that work with refugees in Italy may need to review advocacy strategies and budget for potential legal aid.

Practically, the continued uncertainty means that volumes at mainland reception centres are unlikely to fall in the short term, so appointment backlogs at immigration offices (Questure) may persist through 2025-26. Employers should plan for longer lead-times on permit renewals and factor possible media scrutiny of asylum issues into expatriate-risk briefings.