Belgium has formally requested and received military assistance from France, Germany and the United Kingdom to counter a surge of hostile-drone sightings that have repeatedly closed Brussels and Liège airports over the past week. The decision was confirmed on 10 November after the federal Security Council approved a €50 million emergency budget for new detection and jamming systems.

The foreign detachments include 20 Royal Air Force specialists equipped with portable electronic-warfare kits, French army operators of the “Parade” jamming system, and a German radar team normally assigned to protect G-7 summits. They will deploy alongside Belgium’s small Counter-UAS (C-UAS) squad, which was created in 2021 but lacks enough gear to cover multiple sites simultaneously.

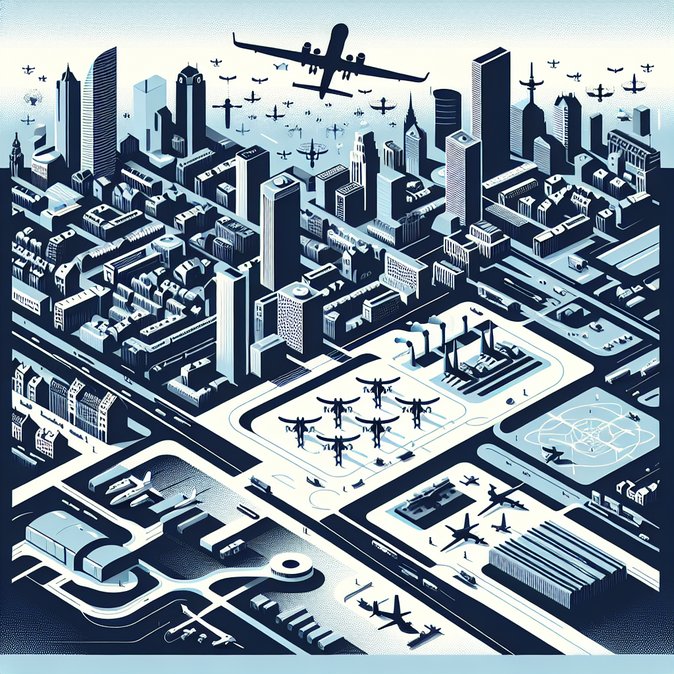

![Belgium Brings In Foreign Anti-Drone Teams After Airport Closures]()

The move follows at least five forced closures of Belgian airspace in the last seven days, culminating in a five-hour shutdown of Brussels Airport on 4 November that stranded more than 20,000 travellers and disrupted dozens of cargo connections for EU supply chains. Officials say some drones were “large, flew in formation and showed military-grade navigation,” raising suspicions of state-sponsored espionage linked to frozen Russian assets held at Brussels-based Euroclear.

For mobility managers the immediate concern is operational continuity: Brussels Airport handles roughly 700 flights and 70,000 passengers a day. Airlines have been told to prepare diversion plans to Amsterdam or Paris at short notice, while logistics providers are rerouting high-value freight through Luxembourg. Employers are advised to add buffer time to itinerary planning, issue safety guidance to assignees and register travellers with their emergency-tracking platforms.

Longer-term, the incident is expected to accelerate EU discussions on a common air-defence overlay for civilian hubs. Belgium’s rapid request for allied help is being hailed inside NATO as a test-case for “plug-and-play” security support—yet it also underscores gaps in Europe’s critical-infrastructure protection that multinationals must now factor into their duty-of-care policies.

The foreign detachments include 20 Royal Air Force specialists equipped with portable electronic-warfare kits, French army operators of the “Parade” jamming system, and a German radar team normally assigned to protect G-7 summits. They will deploy alongside Belgium’s small Counter-UAS (C-UAS) squad, which was created in 2021 but lacks enough gear to cover multiple sites simultaneously.

The move follows at least five forced closures of Belgian airspace in the last seven days, culminating in a five-hour shutdown of Brussels Airport on 4 November that stranded more than 20,000 travellers and disrupted dozens of cargo connections for EU supply chains. Officials say some drones were “large, flew in formation and showed military-grade navigation,” raising suspicions of state-sponsored espionage linked to frozen Russian assets held at Brussels-based Euroclear.

For mobility managers the immediate concern is operational continuity: Brussels Airport handles roughly 700 flights and 70,000 passengers a day. Airlines have been told to prepare diversion plans to Amsterdam or Paris at short notice, while logistics providers are rerouting high-value freight through Luxembourg. Employers are advised to add buffer time to itinerary planning, issue safety guidance to assignees and register travellers with their emergency-tracking platforms.

Longer-term, the incident is expected to accelerate EU discussions on a common air-defence overlay for civilian hubs. Belgium’s rapid request for allied help is being hailed inside NATO as a test-case for “plug-and-play” security support—yet it also underscores gaps in Europe’s critical-infrastructure protection that multinationals must now factor into their duty-of-care policies.